By Bob Caulkins - 1st Provisional DMZ Police Co, 1953 - 1954

At 2200 on 27 July 1953, the 155-mile-long battle line in Korea fell silent. High above every front-line company along the 23-mile sector held by the First Marine Division, white star clusters burst open in the night sky, signaling the end of the fighting. The rockets were not fired in celebration, but in recognition of a cease-fire order from the United Nations Command (UNC).

An uneasy quiet had come to Korea, ancient "Land of the Morning Calm." The war was not ended, only suspended by an armistice between the forces of Communist China and North Korea and the UNC. The 26,000 Marines of Major General Randolph McC. Pate's 1stMarDiv stood down after 36 months of brutal, bloody combat.

The Marines of 1st Provisional DMZ Police Co were constantly manning checkpoints, patrolling and scanning the DMZ, looking for unauthorized incursions in their assigned area. They also escorted members of the United Nations Military Armistice Commission, Joint Observer Teams and members of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission.

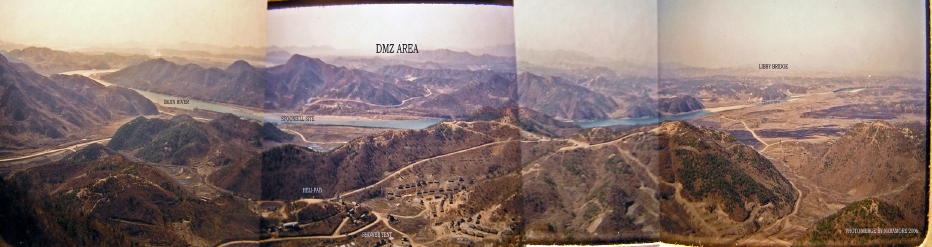

Each side was required by the armistice agreement to withdraw 2,000 meters from their main line of resistance (MLR) positions to create a 4,000-meter-wide Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The DMZ was designed as a buffer between the two opposing enemies to prevent incidents that might lead to a resumption of the fighting. Running through the middle of the DMZ was a demarcation line (DML) separating the communist DMZ from the U.N. DMZ.

An additional requirement was that both the communists and the UNC police their respective zones with "civil police." Because no civilian police were available to either side, the requirement was altered so that specially trained military units could be used.

Thus, on 4 Sept. 1953, the U.S. Marine Corps' 1st Provisional Demilitarized Zone Police Company was established to police the U.N.'s portion of the DMZ. Each regiment of the 1stMarDiv provided 25 enlisted men and one officer. The new unit, which was attached to the Fifth Marine Regiment for logistical support, became operational three days later. A week after that, the new unit's campsite had been built and christened "Camp Semper Fidelis" in honor of the Marines who had been killed in action during the three years of fighting.

The man chosen to lead the new unit was Captain Samuel A. Goich, former commanding officer of "Fox" Co, 2d Battalion, 7th Marines. Capt Goich was a Marine Corps reservist from Chicago, recalled to active duty for the Korean War. Scuttlebutt had it that he had been a time-study engineer (efficiency expert) in civilian life.

Capt Goich's reputed civilian background immediately would be put to the test. The fledgling DMZ Police Co, consisting of only 100 enlisted men and five officers, prepared to patrol the approximately 46-square-mile section of the DMZ, facing off with their North Korean counterparts on the other side of the DML. If one stepped over, capture or death could result.

The DMZ Police Co was a volunteer outfit. Many of the Marines who volunteered did so for the challenge and adventure of belonging to a unit initially described as "a special unit attached to the Northern Regiment." Others did so to avoid the labor of building new trench lines and bunkers for the Division's new defensive positions known as the "Kansas Line," several miles to the rear of the old MLR.

Reporting with record book in hand, each Marine was interviewed by Capt Goich or one of his officers. Applicants had to have a clean record, a General Classification Test score of 95 or above, have at least three months in Korea and preferably be a combat veteran.

The new DMZ Co Marines were briefed on the mission and what was expected of them. The Marines also were given comprehensive classes in the truce agreement and the importance of ensuring the safety of the United Nations Truce Commission personnel, who often entered the DMZ on inspection tours. An equally important mission was to observe the activities of the enemy within the communist sector of the DMZ. Therefore, classes were held on map reading and radio communications. Each DMZ Marine was armed with an M1 rifle and a .45-caliber pistol and was responsible for both weapons.

Many of the hilltops and combat outposts in the old MLR were lost to the communists when the DMZ was established. The result was that some enemy territory could not be seen by units of the Division, which had pulled back 2,000 meters to their new positions on the Kansas Line. Only the DMZ Co Marines had a relatively unobstructed view of enemy positions from their hilltop OPs.

While on the OPs and while patrolling, the Marines were linked by PRC-10 radios to DMZ police headquarters located several miles to the rear. It did not take long for the DMZ Marines to realize that if hostilities were to resume suddenly, the only immediate reporting of enemy troop movements would come from DMZ Co patrols isolated on six or seven hilltop OPs. The military labeled this type of assignment as "The Forlorn Hope."

The majority of DMZ Co were combat veterans of "The Outpost Battles." These battles were around combat outposts Berlin, East Berlin, Carson, Reno, Vegas and Boulder City. The scenes were some of the most violent, close-in, costly combat of the Korean War. Some of these Marines found themselves back on those very hilltops, facing armed enemy soldiers only yards, and sometimes only a few feet, away.

Corporal Walter Steen fought with F/2/7 at Boulder City. He returned to the demolished outpost after the truce as a DMZ policeman. He recalled: "On my first patrol to Boulder City, I almost cried when I saw how much of the hill had been given to the communists; it seemed unfair. During July 1953, 2/7, 1/1 and 3/1 suffered some of the worst casualties of the war, but we held that damned hill!"

Private First Class Richard Mey remembered: "After arriving at the company, I went through the orientation period and then went out on my first patrol in the zone. Three of the guys on the patrol were experienced, but I didn't exactly know what to expect. As we were climbing to the top of a hill where an OP was located, we saw communist DMZ policemen already at the top. What a way to be introduced to the DMZ. This was the enemy! There were no barriers or fences, just a sign that said 'Military Demarcation Line' in English and Korean. When we got to the top of the hill, we were standing literally face to face. They looked at us, and we looked at them, not a word was spoken. After a while they left, and we continued our observations of the enemy side of the DMZ, plotting the location of any enemy activity on a map and then radioing the information in to headquarters."

Tactical and political complications for the DMZ Police Co increased dramatically in October 1953, when 23,000 North Korean and Chinese prisoners of war were resettled in a new POW camp located in the Marine portion of the DMZ near Panmunjom. The prisoners were under the supervision of 5,500 soldiers of the Indian Army Custodial Forces.

The camp was divided into five compounds, and each compound had its own prisoner command structure. Most of the POWs were known to be armed with homemade knives, spears and clubs. For example, there were several thousand flags and banners that the POWs carried at various rallies and demonstrations within the compounds. Every flag and banner had a spear-shaped tip, wrapped in cloth or tissue paper. Underneath these innocent-looking coverings were spear points, made from pieces of steel cut from 55-gallon oil drums and honed to razor sharpness. Rumor also had it that a fairly large supply of firearms had been smuggled into the compounds by sympathetic South Koreans.

These POWs (the vast majority were Chinese) had committed themselves to not returning to their communist homeland. They had announced that they would resist to the death any attempt to force them to go back to Red China.

Cpl Jim Flannigan related, "One day an Indian officer drove up to our OP on Hill 155, which overlooked the POW camp, and told me that several POWs had changed their minds and decided to go back home to Red China. Shortly thereafter, they were murdered by their anticommunist comrades; their bodies were dismembered, and the parts buried throughout the compound."

Although the DMZ Co Marines had no official duties involving the camp or the POWs, their patrols had to pass through the camp to reach a checkpoint situated between the camp and the DML. This checkpoint was called the "Explainer Gate."

The Explainer Gate had been established when the Chinese and North Korean governments were given 90 days to convince the 23,000 POWs who did not wish to return home to change their minds. In order for the "Explainers" to get to the POW camp, they had to cross into the Marine side of the DMZ.

Early each morning, for 90 days, a convoy of Russian jeeps would pull up to the Marine-manned Explainer Gate, and the senior communist, usually a Chinese colonel, would present a list of the names and nationalities of the people in the convoy to a DMZ Police Co officer. The nationalities included Chinese, North Koreans and representatives of the "neutral" nations of Poland and Czechoslovakia. The Marine officer would check the manifest against the people in the convoy. Once the manifest had checked out, the convoy proceeded through the Marine post and into the POW camp. They would exit at the end of the day with the same check of the personnel manifest.

While the explanations were going on, the DMZ Marines also were consolidating their base at Camp Semper Fidelis and becoming more familiar with their demilitarized zone "beat." Many dangers existed in the zone, especially on some of the old fighting positions due to unexploded artillery shells, mortar rounds, hand grenades and antipersonnel mines of both U.N. and communist origin. One DMZ Co patrol was pinned down by ordnance cooking off in a brush fire that had encircled their OP and was burning toward the top of the hill. Most of it was small-arms ammunition; however, several antipersonnel mines or dud mortar shells also detonated. The Marines were forced to take cover in a half-demolished bunker until the fire burned out and the explosions stopped.

Unexploded ordnance was not the only thing that remained in the zone after the truce. In many gullies and draws, where the wind was relatively calm, the smell of death was evident. The corpses of numerous Chinese soldiers were scattered throughout the patrol areas. On several occasions, DMZ Marines were required to escort graves registration details into the U.N. side of the DMZ to investigate various sites where casualties possibly were located. This was an exceptionally dangerous activity; lanes through known minefields had been marked, but heavy rain and high winds obliterated the safe lanes.

The author knows of only one DMZ Marine who died while on duty in the zone in a mine accident. He was escorting a party of infantry Marines who were clearing a pathway along the southern boundary of the DMZ. A mine was tripped; two of the Marines were slightly wounded and another lost an arm. Unfortunately, the DMZ Marine caught a piece of shrapnel in the forehead and was killed instantly. In a second incident, a DMZ Co Marine was seriously wounded by another mine and was evacuated to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) unit.

In late October 1953 because of increased commitments and the mounting number of enemy sightings, the table of organization strength of the company was increased to 314 men and six officers. At the same time, the number of DMZ Marines allowed to operate inside the zone was increased from 50 to 175.

At about that same time, Capt Goich rotated to the States, and the company welcomed Capt Clark Ashton aboard as its new CO. Capt Ashton had been a member of the Palestine-Jordan truce commission and had commanded Marines in Europe and Africa. Prior to taking the helm of the DMZ Co, he had been CO of ceremonial troops at Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C.

In early November 1953, Capt Ashton learned of an upcoming drill competition among all the units of I Corps, which was the senior United States Army command in western Korea. He learned that the contest was to be held in Uijonbu, south of Camp Semper Fidelis. He quickly formed a drill team of 30 enthusiastic volunteers and began an intensive program to train them to perform a Barracks' specialty, an eight-minute silent drill routine. He had only 10 days to do it.

On the day of the competition, the 1st Provisional DMZ Police Co drill team literally "trooped and stomped" the four competing Army drill teams into the dust—even the Army spectators applauded. Capt Ashton was able to finagle a special R&R in Japan for the victorious DMZ team.

On 10 Nov. 1953, the DMZ Co celebrated the Corps' 178th birthday in its own slopchute, constructed by hook or crook, sweat and numerous midnight requisitions. Over the polished, plywood bar hung a mural of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which was contrasted by the red, neonlike wallpaper. After the appropriate toasts to Corps and country and the cutting of the birthday cake, the champagne corks began popping. Entertainment consisted of the 5th Marines' chaplain playing jazz selections on his trumpet. He used an empty beer can as a mute to play "Sugar Blues." A good time was had by all, even if the outside temperature was 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

In late January 1954, the 90-day period of explanations came to a close. Of the 23,000 prisoners being held in the POW camp, only 137 were persuaded by the communist explainers to change their minds and return home. It now became crucial that the remaining thousands of Chinese POWs be quickly evacuated south to Inchon for transport to Formosa (present-day Taiwan). Any delay might prompt the POWs to think that the United Nations was abandoning them to the tender mercies of their former communist masters, resulting in a mass breakout attempt with the accompanying bloodshed.

The DMZ Police Co was chosen by the U.N. Command to assist in the evacuation of the prisoners. On 23 Jan. 1954, DMZ Marines moved into each camp compound, separating the POWs into groups of 500, with one Marine in charge of each group. When directed, the lone Marine, armed with a .45-cal. pistol and M1 rifle with fixed bayonet, would gesture to his 500 squatting charges to stand up and follow him. The Marine then would march the POWs out of the camp to the railhead to board the train to Inchon.

The loading of prisoners onto several trains lasted from early in the morning of 23 Jan. until late into a rainy, windy night. Many of the Marines came away with souvenir homemade flags presented to them by the grateful Chinese "ex-prisoners."

Once the prisoners had departed South Korea, the job of the Indian Custodial Force was finished, and they prepared to head back to India. Shortly before leaving, a jeep with four Indian soldiers ran off a road and turned over, pinning the soldiers under the jeep in several feet of water. A quick-acting DMZ Marine jumped into the water and succeeded in freeing two of the soldiers; unfortunately, the other two died. Several days after the event, Indian officers paid a visit to Camp Semper Fidelis and presented the Marine with a beautiful serving tray, inlaid with pearl and precious stones, in gratitude for his heroic act.

By the end of the POW episode, deep winter had settled in with temperatures often down to 15 to 20 degrees below zero. The weather, however, did not curtail the patrol, observation or security duties of DMZ Co. Day and night, Marines stood watch on frigid, snow-blown hilltop observation posts and patrolled in areas determined to be favorable terrain for infiltrators or line-crossers.

Many line-crossers were Koreans trying to reach their homes in the north or south. Some, however, were North Korean agents trying to infiltrate into South Korea on intelligence missions or trying to return to North Korea after fulfilling their missions.

Several probable agents were apprehended, along with a good number of deserters who surrendered to the Marines and took their weapons with them, which made the situation a bit tense.

The company became a magnet for visiting dignitaries. The Secretary of the Navy, the Commandant of the Marine Corps and numerous other military personnel dropped in almost on a weekly basis. They were picked up at the company helipad with a jeep polished with shoe polish (there was no auto wax available) and driven to the company CP to be greeted by a DMZ Co honor guard.

Until March 1955, the DMZ Police Co continued to perform its exacting, strenuous, and often dangerous duties within the DMZ.

In the latter part of March 1955, with the impending departure of the 1stMarDiv from Korea, a demilitarized zone police company from the Army's 24th Infantry Division relieved the 1st Provisional Demilitarized Zone Police Co. The relief ceremonies were held at 1st Mar Div headquarters and witnessed by senior members of the United Nations Command and the President of South Korea, Syngman Rhee.

The DMZ Marines had made a difference. Thrust suddenly into a situation where the slightest misstep might have precipitated a resumption in the fighting, the leathernecks were dedicated, knowledgeable and highly adaptable in a fluid situation. They performed their frequently dangerous duty with honor and courage.

Unfortunately, recognition for a job well done was not to be. Although members of the DMZ Co initially were recognized with a Letter of Commendation signed by the commanding general of the 1stMarDiv, the letters were withdrawn several years later without explanation.

Except for a brief mention in "U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, Volume V" and an article in Leatherneck magazine in February 1954, the company faded into obscure Marine Corps history. In the pensive words of a Marine who served with the company up to its relief by the 24th Infantry Div:

"A couple of days after the relief ceremonies, we boarded ships at Inchon and headed for the United States. When we arrived at San Diego, we were broken up and scattered to units throughout the Corps, and the 1st Provisional Demilitarized Zone Police Company ceased to exist. Amen."

At 2200 on 27 July 1953, the 155-mile-long battle line in Korea fell silent. High above every front-line company along the 23-mile sector held by the First Marine Division, white star clusters burst open in the night sky, signaling the end of the fighting. The rockets were not fired in celebration, but in recognition of a cease-fire order from the United Nations Command (UNC).

An uneasy quiet had come to Korea, ancient "Land of the Morning Calm." The war was not ended, only suspended by an armistice between the forces of Communist China and North Korea and the UNC. The 26,000 Marines of Major General Randolph McC. Pate's 1stMarDiv stood down after 36 months of brutal, bloody combat.

The Marines of 1st Provisional DMZ Police Co were constantly manning checkpoints, patrolling and scanning the DMZ, looking for unauthorized incursions in their assigned area. They also escorted members of the United Nations Military Armistice Commission, Joint Observer Teams and members of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission.

Each side was required by the armistice agreement to withdraw 2,000 meters from their main line of resistance (MLR) positions to create a 4,000-meter-wide Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The DMZ was designed as a buffer between the two opposing enemies to prevent incidents that might lead to a resumption of the fighting. Running through the middle of the DMZ was a demarcation line (DML) separating the communist DMZ from the U.N. DMZ.

An additional requirement was that both the communists and the UNC police their respective zones with "civil police." Because no civilian police were available to either side, the requirement was altered so that specially trained military units could be used.

Thus, on 4 Sept. 1953, the U.S. Marine Corps' 1st Provisional Demilitarized Zone Police Company was established to police the U.N.'s portion of the DMZ. Each regiment of the 1stMarDiv provided 25 enlisted men and one officer. The new unit, which was attached to the Fifth Marine Regiment for logistical support, became operational three days later. A week after that, the new unit's campsite had been built and christened "Camp Semper Fidelis" in honor of the Marines who had been killed in action during the three years of fighting.

The man chosen to lead the new unit was Captain Samuel A. Goich, former commanding officer of "Fox" Co, 2d Battalion, 7th Marines. Capt Goich was a Marine Corps reservist from Chicago, recalled to active duty for the Korean War. Scuttlebutt had it that he had been a time-study engineer (efficiency expert) in civilian life.

Capt Goich's reputed civilian background immediately would be put to the test. The fledgling DMZ Police Co, consisting of only 100 enlisted men and five officers, prepared to patrol the approximately 46-square-mile section of the DMZ, facing off with their North Korean counterparts on the other side of the DML. If one stepped over, capture or death could result.

The DMZ Police Co was a volunteer outfit. Many of the Marines who volunteered did so for the challenge and adventure of belonging to a unit initially described as "a special unit attached to the Northern Regiment." Others did so to avoid the labor of building new trench lines and bunkers for the Division's new defensive positions known as the "Kansas Line," several miles to the rear of the old MLR.

Reporting with record book in hand, each Marine was interviewed by Capt Goich or one of his officers. Applicants had to have a clean record, a General Classification Test score of 95 or above, have at least three months in Korea and preferably be a combat veteran.

The new DMZ Co Marines were briefed on the mission and what was expected of them. The Marines also were given comprehensive classes in the truce agreement and the importance of ensuring the safety of the United Nations Truce Commission personnel, who often entered the DMZ on inspection tours. An equally important mission was to observe the activities of the enemy within the communist sector of the DMZ. Therefore, classes were held on map reading and radio communications. Each DMZ Marine was armed with an M1 rifle and a .45-caliber pistol and was responsible for both weapons.

Many of the hilltops and combat outposts in the old MLR were lost to the communists when the DMZ was established. The result was that some enemy territory could not be seen by units of the Division, which had pulled back 2,000 meters to their new positions on the Kansas Line. Only the DMZ Co Marines had a relatively unobstructed view of enemy positions from their hilltop OPs.

While on the OPs and while patrolling, the Marines were linked by PRC-10 radios to DMZ police headquarters located several miles to the rear. It did not take long for the DMZ Marines to realize that if hostilities were to resume suddenly, the only immediate reporting of enemy troop movements would come from DMZ Co patrols isolated on six or seven hilltop OPs. The military labeled this type of assignment as "The Forlorn Hope."

The majority of DMZ Co were combat veterans of "The Outpost Battles." These battles were around combat outposts Berlin, East Berlin, Carson, Reno, Vegas and Boulder City. The scenes were some of the most violent, close-in, costly combat of the Korean War. Some of these Marines found themselves back on those very hilltops, facing armed enemy soldiers only yards, and sometimes only a few feet, away.

Corporal Walter Steen fought with F/2/7 at Boulder City. He returned to the demolished outpost after the truce as a DMZ policeman. He recalled: "On my first patrol to Boulder City, I almost cried when I saw how much of the hill had been given to the communists; it seemed unfair. During July 1953, 2/7, 1/1 and 3/1 suffered some of the worst casualties of the war, but we held that damned hill!"

Private First Class Richard Mey remembered: "After arriving at the company, I went through the orientation period and then went out on my first patrol in the zone. Three of the guys on the patrol were experienced, but I didn't exactly know what to expect. As we were climbing to the top of a hill where an OP was located, we saw communist DMZ policemen already at the top. What a way to be introduced to the DMZ. This was the enemy! There were no barriers or fences, just a sign that said 'Military Demarcation Line' in English and Korean. When we got to the top of the hill, we were standing literally face to face. They looked at us, and we looked at them, not a word was spoken. After a while they left, and we continued our observations of the enemy side of the DMZ, plotting the location of any enemy activity on a map and then radioing the information in to headquarters."

Tactical and political complications for the DMZ Police Co increased dramatically in October 1953, when 23,000 North Korean and Chinese prisoners of war were resettled in a new POW camp located in the Marine portion of the DMZ near Panmunjom. The prisoners were under the supervision of 5,500 soldiers of the Indian Army Custodial Forces.

The camp was divided into five compounds, and each compound had its own prisoner command structure. Most of the POWs were known to be armed with homemade knives, spears and clubs. For example, there were several thousand flags and banners that the POWs carried at various rallies and demonstrations within the compounds. Every flag and banner had a spear-shaped tip, wrapped in cloth or tissue paper. Underneath these innocent-looking coverings were spear points, made from pieces of steel cut from 55-gallon oil drums and honed to razor sharpness. Rumor also had it that a fairly large supply of firearms had been smuggled into the compounds by sympathetic South Koreans.

These POWs (the vast majority were Chinese) had committed themselves to not returning to their communist homeland. They had announced that they would resist to the death any attempt to force them to go back to Red China.

Cpl Jim Flannigan related, "One day an Indian officer drove up to our OP on Hill 155, which overlooked the POW camp, and told me that several POWs had changed their minds and decided to go back home to Red China. Shortly thereafter, they were murdered by their anticommunist comrades; their bodies were dismembered, and the parts buried throughout the compound."

Although the DMZ Co Marines had no official duties involving the camp or the POWs, their patrols had to pass through the camp to reach a checkpoint situated between the camp and the DML. This checkpoint was called the "Explainer Gate."

The Explainer Gate had been established when the Chinese and North Korean governments were given 90 days to convince the 23,000 POWs who did not wish to return home to change their minds. In order for the "Explainers" to get to the POW camp, they had to cross into the Marine side of the DMZ.

Early each morning, for 90 days, a convoy of Russian jeeps would pull up to the Marine-manned Explainer Gate, and the senior communist, usually a Chinese colonel, would present a list of the names and nationalities of the people in the convoy to a DMZ Police Co officer. The nationalities included Chinese, North Koreans and representatives of the "neutral" nations of Poland and Czechoslovakia. The Marine officer would check the manifest against the people in the convoy. Once the manifest had checked out, the convoy proceeded through the Marine post and into the POW camp. They would exit at the end of the day with the same check of the personnel manifest.

While the explanations were going on, the DMZ Marines also were consolidating their base at Camp Semper Fidelis and becoming more familiar with their demilitarized zone "beat." Many dangers existed in the zone, especially on some of the old fighting positions due to unexploded artillery shells, mortar rounds, hand grenades and antipersonnel mines of both U.N. and communist origin. One DMZ Co patrol was pinned down by ordnance cooking off in a brush fire that had encircled their OP and was burning toward the top of the hill. Most of it was small-arms ammunition; however, several antipersonnel mines or dud mortar shells also detonated. The Marines were forced to take cover in a half-demolished bunker until the fire burned out and the explosions stopped.

Unexploded ordnance was not the only thing that remained in the zone after the truce. In many gullies and draws, where the wind was relatively calm, the smell of death was evident. The corpses of numerous Chinese soldiers were scattered throughout the patrol areas. On several occasions, DMZ Marines were required to escort graves registration details into the U.N. side of the DMZ to investigate various sites where casualties possibly were located. This was an exceptionally dangerous activity; lanes through known minefields had been marked, but heavy rain and high winds obliterated the safe lanes.

The author knows of only one DMZ Marine who died while on duty in the zone in a mine accident. He was escorting a party of infantry Marines who were clearing a pathway along the southern boundary of the DMZ. A mine was tripped; two of the Marines were slightly wounded and another lost an arm. Unfortunately, the DMZ Marine caught a piece of shrapnel in the forehead and was killed instantly. In a second incident, a DMZ Co Marine was seriously wounded by another mine and was evacuated to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) unit.

In late October 1953 because of increased commitments and the mounting number of enemy sightings, the table of organization strength of the company was increased to 314 men and six officers. At the same time, the number of DMZ Marines allowed to operate inside the zone was increased from 50 to 175.

At about that same time, Capt Goich rotated to the States, and the company welcomed Capt Clark Ashton aboard as its new CO. Capt Ashton had been a member of the Palestine-Jordan truce commission and had commanded Marines in Europe and Africa. Prior to taking the helm of the DMZ Co, he had been CO of ceremonial troops at Marine Barracks, Washington, D.C.

In early November 1953, Capt Ashton learned of an upcoming drill competition among all the units of I Corps, which was the senior United States Army command in western Korea. He learned that the contest was to be held in Uijonbu, south of Camp Semper Fidelis. He quickly formed a drill team of 30 enthusiastic volunteers and began an intensive program to train them to perform a Barracks' specialty, an eight-minute silent drill routine. He had only 10 days to do it.

On the day of the competition, the 1st Provisional DMZ Police Co drill team literally "trooped and stomped" the four competing Army drill teams into the dust—even the Army spectators applauded. Capt Ashton was able to finagle a special R&R in Japan for the victorious DMZ team.

On 10 Nov. 1953, the DMZ Co celebrated the Corps' 178th birthday in its own slopchute, constructed by hook or crook, sweat and numerous midnight requisitions. Over the polished, plywood bar hung a mural of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which was contrasted by the red, neonlike wallpaper. After the appropriate toasts to Corps and country and the cutting of the birthday cake, the champagne corks began popping. Entertainment consisted of the 5th Marines' chaplain playing jazz selections on his trumpet. He used an empty beer can as a mute to play "Sugar Blues." A good time was had by all, even if the outside temperature was 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

In late January 1954, the 90-day period of explanations came to a close. Of the 23,000 prisoners being held in the POW camp, only 137 were persuaded by the communist explainers to change their minds and return home. It now became crucial that the remaining thousands of Chinese POWs be quickly evacuated south to Inchon for transport to Formosa (present-day Taiwan). Any delay might prompt the POWs to think that the United Nations was abandoning them to the tender mercies of their former communist masters, resulting in a mass breakout attempt with the accompanying bloodshed.

The DMZ Police Co was chosen by the U.N. Command to assist in the evacuation of the prisoners. On 23 Jan. 1954, DMZ Marines moved into each camp compound, separating the POWs into groups of 500, with one Marine in charge of each group. When directed, the lone Marine, armed with a .45-cal. pistol and M1 rifle with fixed bayonet, would gesture to his 500 squatting charges to stand up and follow him. The Marine then would march the POWs out of the camp to the railhead to board the train to Inchon.

The loading of prisoners onto several trains lasted from early in the morning of 23 Jan. until late into a rainy, windy night. Many of the Marines came away with souvenir homemade flags presented to them by the grateful Chinese "ex-prisoners."

Once the prisoners had departed South Korea, the job of the Indian Custodial Force was finished, and they prepared to head back to India. Shortly before leaving, a jeep with four Indian soldiers ran off a road and turned over, pinning the soldiers under the jeep in several feet of water. A quick-acting DMZ Marine jumped into the water and succeeded in freeing two of the soldiers; unfortunately, the other two died. Several days after the event, Indian officers paid a visit to Camp Semper Fidelis and presented the Marine with a beautiful serving tray, inlaid with pearl and precious stones, in gratitude for his heroic act.

By the end of the POW episode, deep winter had settled in with temperatures often down to 15 to 20 degrees below zero. The weather, however, did not curtail the patrol, observation or security duties of DMZ Co. Day and night, Marines stood watch on frigid, snow-blown hilltop observation posts and patrolled in areas determined to be favorable terrain for infiltrators or line-crossers.

Many line-crossers were Koreans trying to reach their homes in the north or south. Some, however, were North Korean agents trying to infiltrate into South Korea on intelligence missions or trying to return to North Korea after fulfilling their missions.

Several probable agents were apprehended, along with a good number of deserters who surrendered to the Marines and took their weapons with them, which made the situation a bit tense.

The company became a magnet for visiting dignitaries. The Secretary of the Navy, the Commandant of the Marine Corps and numerous other military personnel dropped in almost on a weekly basis. They were picked up at the company helipad with a jeep polished with shoe polish (there was no auto wax available) and driven to the company CP to be greeted by a DMZ Co honor guard.

Until March 1955, the DMZ Police Co continued to perform its exacting, strenuous, and often dangerous duties within the DMZ.

In the latter part of March 1955, with the impending departure of the 1stMarDiv from Korea, a demilitarized zone police company from the Army's 24th Infantry Division relieved the 1st Provisional Demilitarized Zone Police Co. The relief ceremonies were held at 1st Mar Div headquarters and witnessed by senior members of the United Nations Command and the President of South Korea, Syngman Rhee.

The DMZ Marines had made a difference. Thrust suddenly into a situation where the slightest misstep might have precipitated a resumption in the fighting, the leathernecks were dedicated, knowledgeable and highly adaptable in a fluid situation. They performed their frequently dangerous duty with honor and courage.

Unfortunately, recognition for a job well done was not to be. Although members of the DMZ Co initially were recognized with a Letter of Commendation signed by the commanding general of the 1stMarDiv, the letters were withdrawn several years later without explanation.

Except for a brief mention in "U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, Volume V" and an article in Leatherneck magazine in February 1954, the company faded into obscure Marine Corps history. In the pensive words of a Marine who served with the company up to its relief by the 24th Infantry Div:

"A couple of days after the relief ceremonies, we boarded ships at Inchon and headed for the United States. When we arrived at San Diego, we were broken up and scattered to units throughout the Corps, and the 1st Provisional Demilitarized Zone Police Company ceased to exist. Amen."